Reza Aramesh & Homa Delvaray: Frieze London 2022

A duo presentation of works by Reza Aramesh and Homa Delvaray at Frieze London 2022, Booth A10, presented by Dastan Gallery.

At Frieze London 2022, Dastan exhibits a duo presentation of works by two prominent contemporary Iranian artists, Homa Delvaray and Reza Aramesh.

Following on “Soft Edge of the Blade”, which was featured at Frieze’s No. 9 Cork Street (London, UK) in February 2022, this duo continues to expand on the idea of the artistic expression of externally-induced violence, often focusing on its paradoxically ‘soft’, symbolic, hidden, or underlying guises, as well as more recognizable forms.

The outlook is not limited to the more obviously-visible larger-scale violence of war or political oppression. The intended scope is broader and more subtle, extending to numerous more insidious forms of violence affecting Iranians over the past half a century: from the most brutal and naked shows of power, be them domestically or internationally, to its more indirect consequences in issues such as migration and diaspora, identity and gender, patriarchy and family, and the impact of the complexities of history on the day-to-day life of Iranians, the use of language to disparage or oppress, as well as other less conspicuous discourses and their connotations.

In the current presentation, the two artists have explored this idea simultaneously over several layers: Reza Aramesh, by layering his interpretation over the anonymity of a marginalized class, challenging the glorification of nobility, and Homa Delvaray by focusing on a satirical critique of superstition and extending its reading over a global discourse.

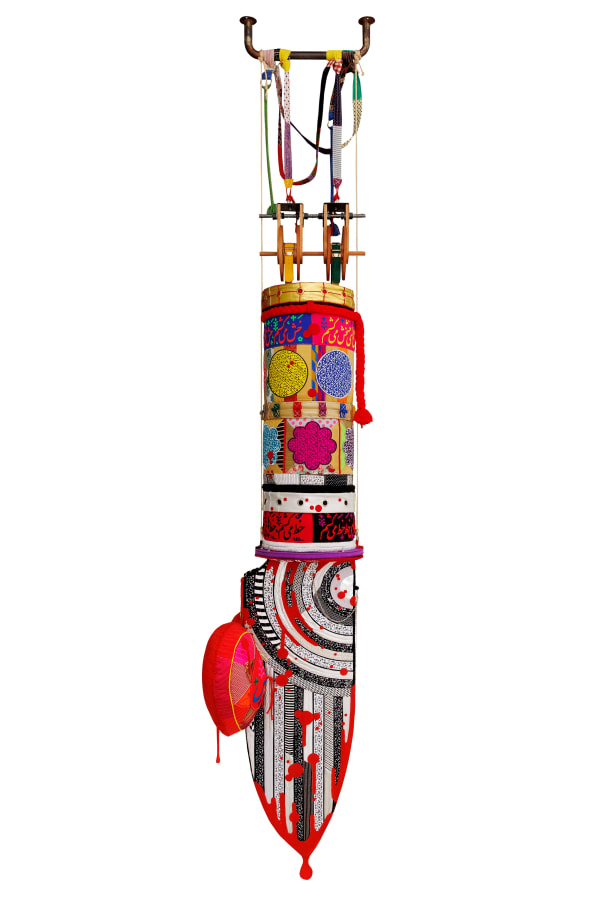

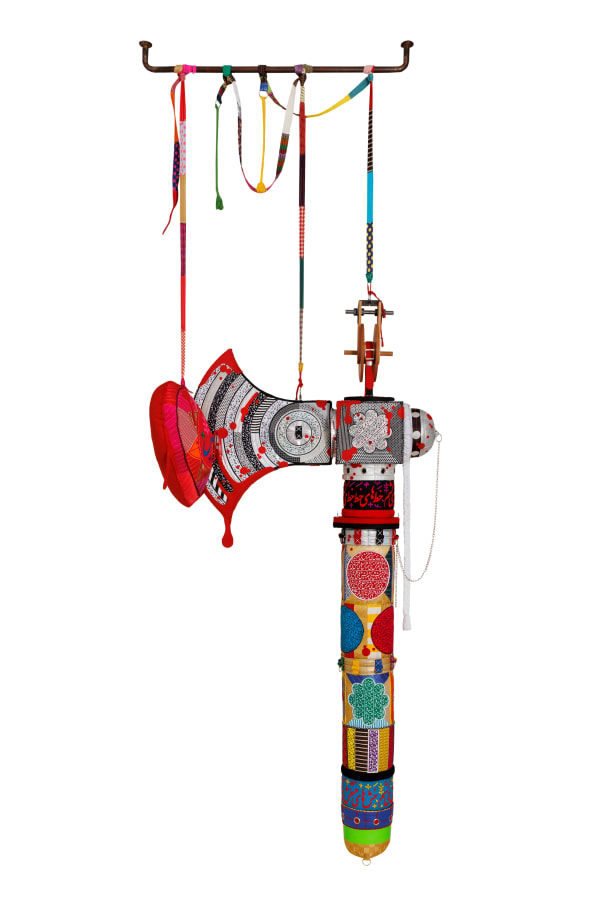

In her most recent pieces, Homa Delvaray continues her studies on “Kitábi Kulśum Naneh”, an early 18th century book by Aqa Jamal Khwansari, a prominent Iranian cleric of his time. This book is a sarcastic review of superstitious beliefs and acts attributed to Iranian women of the Safavid Period, and aims to use a satirical language in its criticism of such traditions and differentiate between superstition and true religious beliefs. Homa’s work focuses on the book’s account of one such superstitious ritual: the territorialization of a pregnant woman’s area in order to keep diseases and evil spirits away: Aqa Jamal Khwansari writes* that “Kulśum Naneh says, if these marks are not drawn as prescribed, the apprehended disease will come on violently, and the woman undoubtedly die” **.

In the book, it is written that the ritual involves using such sharp metal tools as scissors, knives and swords, to ‘draw a border’ around the pregnant woman while reciting spells and magic expressions, including repeating the phrase “I scratch, I scratch, I draw scratchy scratches” and specifically telling the woman that they ‘scratched’ the border, instead of saying they ‘lined’ it. This is meant as a distraction, in order to deceive evil spirits. The book’s satirical account of the ritual is meant to show its absurdity, and the play of words (‘scratch’ vs. ‘line’; “Khash” vs. “Khat” in the original Persian) symbolically refers to the contrast between ‘superstitious beliefs’ and taking a ‘rational’ approach.

The same contrast, and the variety of paradoxical interpretations the account ensues, was one of the key inspirations in Homa Delvaray’s recent works. The pieces depict four cutting tools (knife, sword, pick, axe) as three-dimensional sculptures finished in fabrics. Each of these tools has a body and a cutting area: the body is finished in pieces of fabric repeating, in traditional Nastaliq type, the words “I scratch, I scratch, I draw scratchy scratches”, while on the cutting area depicts the words “I draw lines, I draw lines, I draw linear lines”. The sharp edges of these tools target a symbolic heart showing the word “Khash” (‘scratch’), playing on the idea of a soft fighting between ideas and approaches. While Homa has transformed these sharp tools using domestic decorations that suppress their violent potential, this approach ultimately presents a global reality: an often complicated and convoluted conflict among fundamentally-different belief systems and the fight over which bears the most truth.

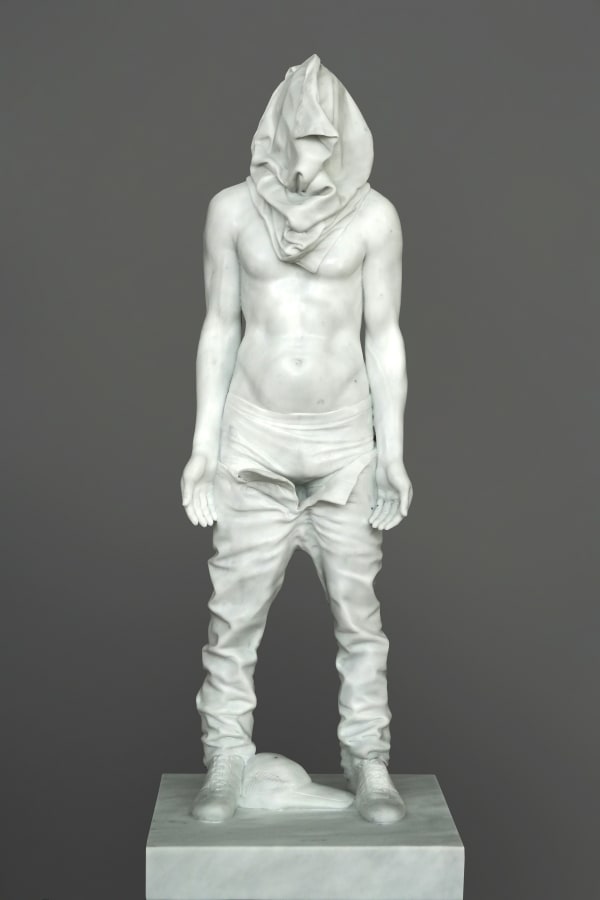

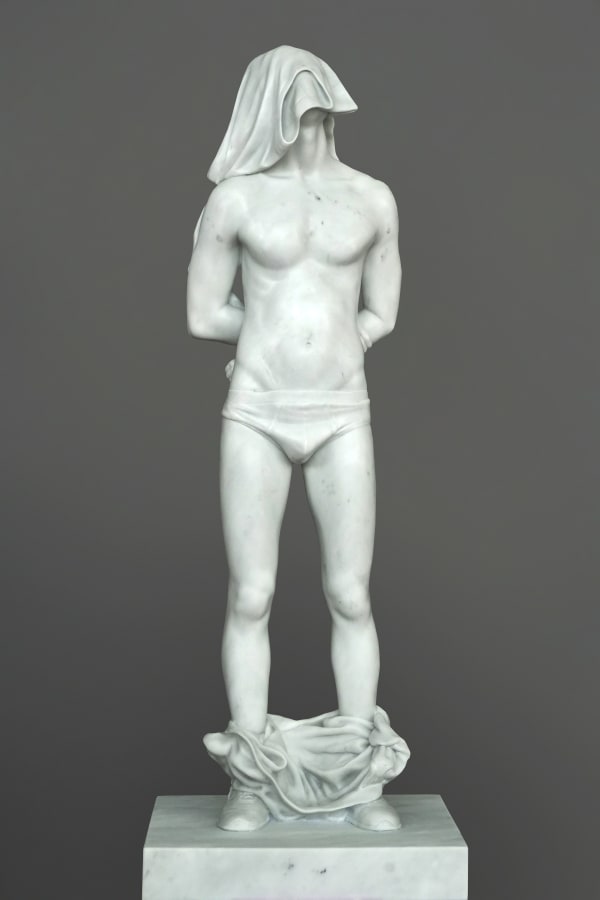

On the other hand, Reza Aramesh’s four sculptures, which are part of his ongoing “Site of the Fall: Study of the Renaissance Garden” series, focus on a different reality whose reach and effects are continuing to expand into more layers of our thoughts and understanding of the world around us: the media’s depiction of violence, as well as the interpretations of images presented by the media.

Reza’s sculptures are the result of an extensive research on reports and images of war and conflict. Scouring through online databases, books and publications, newspapers articles, journals and magazines, the artist extracts images of figures and poses that he aims to reenact. He de-contextualizes scenes of historical and contemporary moments, exploring the narrative between the representation of subjected bodies, mythologizing history as well as beauty in iconography.

Under the artist’s direction, a model is captured using digital photography and three- dimensional scan technology. Subsequently, the data from the scans is used to create a hand-carved human figure out of Carrara white marble. As so, for Aramesh, a singled-out image becomes the original material for the final sculpture, with his profound understanding of the history of art, film and literature guiding him along the way.

Aramesh’s “Site of the Fall: Study of the Renaissance Garden” series intends to create conversations with and reference to Western understandings of anguish and survival, as represented in Renaissance iconography and especially through the figure of Saint Sebastian. Unlike Renaissance statues which were often depictions of noble men, holy icons or mythological figures, these sculptures are often depictions of working class, people of color and vulnerable men from the Middle East, Asia and Africa. As so, by creating this body of work the artist sets out to challenge the absence of others within the discourse of Western Art history. Meticulously hand-carved from a precious stone, the Carrara white marble, they are meant to glorify the everyday man, representing strength, resilience and power.

* It is noteworthy that Aqa Jamal Khwansari uses a feminine figure, that is Kulśum Naneh, as both the narrator and authority, distancing himself away from the narrative and attributing the superstitious beliefs to Iranian “women” of the time.

** Atkinson, James. 1832. “Kitábi Kulśum Naneh: Customs and Manners of the Women of Persia, and their Domestic Superstitions”. London: J.L. Cox for Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland.