Sadra Baniasadi Iranian, b. 1991

Overview

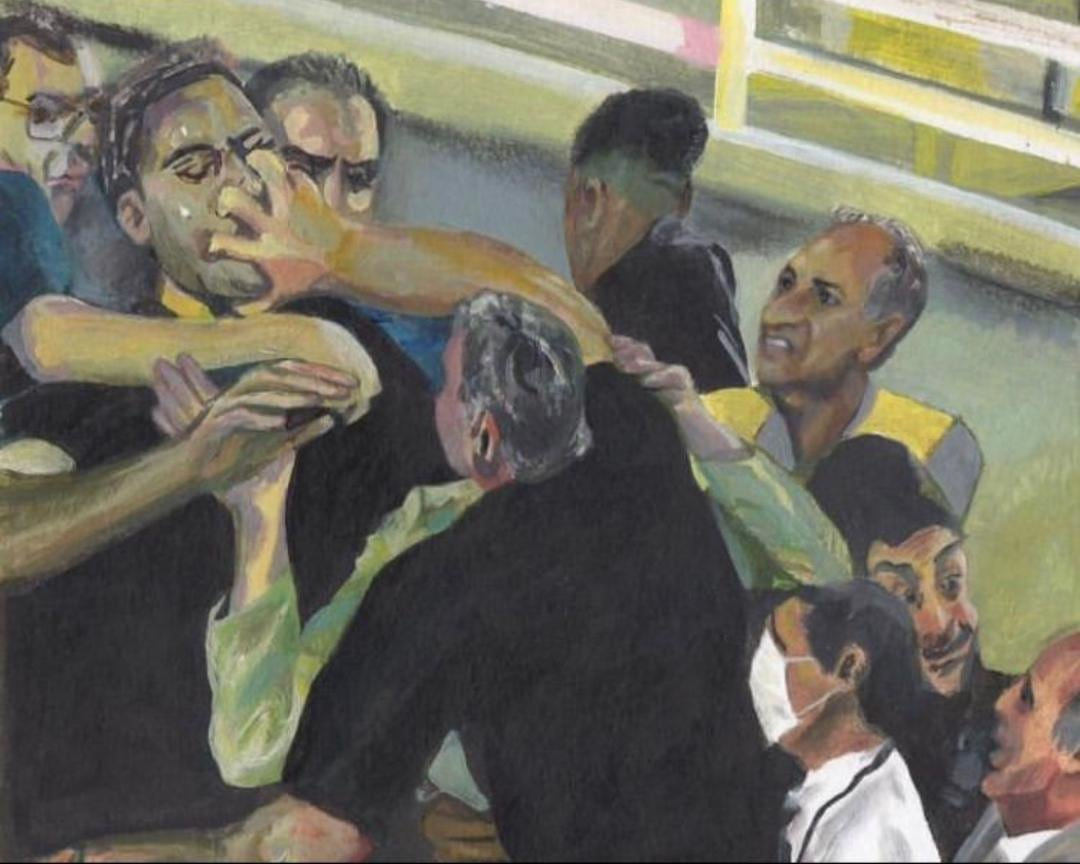

It is not often, in the peresent moment, that one hears an artist is making religious art, without irony, and rarer still when the work that follows remains inviting rather than doctrinal. Sadra Baniasadi another painter-prophet, alike to Mani, has the patience of someone who has accepted the burden of a narrative role rather than the comfort of a novel pioneer.

Born a Virgo in 1990, Tehran, into a family of artists, with both father (Mohammad Ali Baniasadi) and grandfather shaping his earliest sense of what it meant to paint, Sadra grew up within a quiet familiarity with images and their habits. During his studies at Tehran’s School of Fine Arts and later the University of Art his work was not welcomed academically, none of his teachers could stomach it, often warning him of ending up like his father; an illustrator. The narrative insistence of his work often met a restrained resistance, a friction that seemed less to divert him than to confirm the necessity of pursuing a more private and continuous path. Perhaps this was what drew him to take his images in a sticker format to the streets plastered over the city, forming a community with the outcast graffiti artists.

His work does not lay easily on a sepctrum, if one could consider any, of representation and abstraction, but moves instead within a quieter territory where form yields to the pressure of story, as the likes of Giotto in the early Christian images, in their reliance on narrative over description. What appears is less a record of how a thing looks than an evocation of what it leaves behind in the mind, the remembered trace of an essence rather than its visible outline.

Sadra’s studio, crowded with devotional images of the Holy Mary, beads (Tasbīḥ), iconographic carpets of Imam Ali, and books on Indian Religions, suggests a research-based devotion to sources, yet the paintings resist the polished inevitability that often accompanies such preparation. The ease with which he absorbs these icons of other religions could have not satisfy his temptaion for creating his own. This is where his private religion, with its mirrored gods of image and sound, of surface and air, begins to feel less like a system than a method, a way of thinking through painting rather than about it.

There is a certain quiet courage in this, a willingness to accept being dismissed as naïve, illustrative, or inopportune, and to continue nonetheless, guided by an interior rhythm that does not seek permission. The paintings do not demand belief from the viewer.

Works

Exhibitions

-

Group Presentation | "Soft Edge of the Blade Vol. 3"

Zaal x Leila Heller 11 Nov 2025 - 8 Jan 2026 ZaalZaal Art Gallery, in collaboration with Leila Heller Gallery, proudly presents Soft Edge of the Blade Vol. 3 , on view from November 11 to January 8. Curated by Mamali...Read more -

Sadra Baniasadi | "Escaping Reality, Full Speed"

Dastan's Basement 3 - 24 May 2024 The BasementA solo exhibition of works by Sadra Baniasadi at Dastan's Basement.Read more -

Sadra Baniasadi | "Sisters"

Dastan's Basement 29 Nov - 20 Dec 2019 The BasementA solo presentation of works by Sadra BaniasadiRead more -

Teer Art Fair 2018

Teer Art Fair 2018 24 - 30 Jun 2018 Art FairsDastan's Presentation at the first edition of TeerArtRead more -

Sadra Baniasadi | "Outdated"

Dastan's Basement 5 - 19 Jan 2018 The BasementSolo painting and drawing exhibition of recent works by Sadra BaniasadiRead more -

"The Universal Pink"

Untitled Art, Miami Beach 2017 6 - 10 Dec 2017 Art FairsA curated booth titled “The Universal Pink” consisting of works by Sam Samiee, Farrokh Mahdavi and Sadra Bani-AsadiRead more -

"A Camp"

Dastan's Basement 13 - 27 Oct 2017 The BasementAn installation of various artwoks by Manijeh Akhavan, Sadra Bani-Asadi, Serminaz Barseghian, Aylar Dastgiri, and Sam SamieeRead more -

Inspired by "References, Clues and Favorite Things" | Curated by Fereydoun Ave

Art Dubai 2017 12 - 18 Mar 2017 Art FairsA presentation inspired by Fereydoun Ave's project "References, Clues, and Favorite Things"Read more -

"Update"

Dastan +2 30 Sep - 16 Oct 2016 +2 [ Fereshteh ]Group Exhibition of Dastan's ArtistsRead more -

Sadra Baniasadi | "Dog Language"

Dastan's Basement 5 - 13 Feb 2016 The BasementA solo exhibition of works by Sadra BaniasadiRead more -

''Year in Review''

Dastan:Outside | Sam Art 13 - 17 Mar 2015 Dastan:OutsideYear in Review Over the past year, Dastan has held 25 exhibitions inside and outside the Basement. This year also marked the opening of Sam Art, a pop-up space, dedicated...Read more -

Sadra Baniasadi, Arash Qeluich & Surena Petgar | "3 in One"

Dastan's Basement 2 - 10 Jan 2015 The BasementGroup Exhibition of Works by Sadra Baniasadi, Arash Qeluich & Surena Petgar at Dastan's BasementRead more